|

|

|

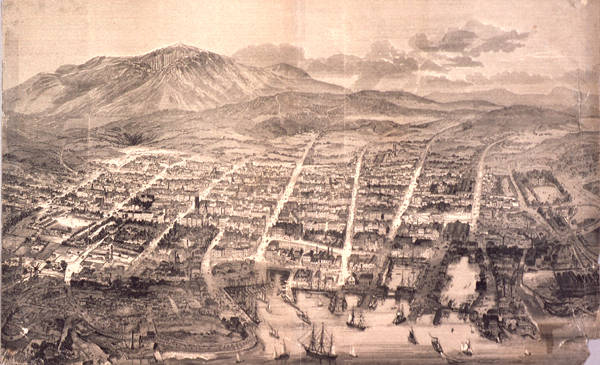

Hobart

Hobart was founded in 1804, when Lt-Governor Collins moved the main southern settlement from Risdon to Sullivan's Cove. This was an excellent site, with a good port, good fresh water, and the shelter of Mount Wellington. From that date Hobart has been the capital and administrative centre of first southern Tasmania, then from 1812 all Tasmania. This meant parliament and government departments, major educational establishments and the headquarters of churches and many businesses and groups have been established in Hobart. It has been Tasmania's largest urban centre, with roughly double the population of the next largest, Launceston. Lack of food and equipment dogged Hobart's first years, but gradually a town developed. The port grew, home to sealers and whalers – whaling began in the Derwent in 1804. By 1811, when Governor Macquarie ordered a town plan, Hobart, though still small, boasted hotels and shops, a church, hospital, quarry and newspaper, and some substantial houses. Local industries were established, such as milling, brewing, tanning and shipbuilding. The 1820s saw development, with more efficient administrators and some energetic free settlers and ex-convicts. Merchants developed trade, with Hobart a major port for the developing wool trade; shops grew; and fine Georgian sandstone buildings were erected, such as a Presbyterian church (1824), Salamanca Place warehouses (1830s), the Theatre Royal (1837) and private homes like Narryna (1828) and Westella (1835). Settlement extended to outlying areas such as Sandy Bay, South Hobart, West Hobart and New Town. As the seat of government, Hobart also gained official buildings such as the Treasury. Recreations developed: cricket, an annual regatta, and yachting on the Derwent. The busy port and the preponderence of convicts in the population meant that Hobart was still 'wild and unruly' with a high crime rate. By the 1840s, it 'began to take on the guise of a town', and it was declared a city in 1842. When it became a municipality in 1852 it had 24,000 people, the third largest city in Australia. Between 1852 and 1914 there were significant changes to Hobart's political and social landscape. Politically, Hobart was conservative until the 1880s when liberalism asserted itself, through newspapers like the Tasmanian News, attacking the property-dominated Hobart Corporation, which was supported by the Mercury. Labor politicians and the growing trade union movement supported many reforms after 1900 and their organ, the Clipper, was an astringent and humorous critic of municipal politics. Pressure groups agitated for reform and positive changes were made in cleaning up the city, dealing with insanitary housing and providing a sewerage system. As a result, infectious diseases, especially typhoid, declined. The Hobart General Hospital (Royal Hobart Hospital), Homeopathic Hospital and friendly societies helped Hobartians in time of sickness or infirmity. Life improved in other ways. When the Town Hall was opened in 1866 it symbolised the hope of future greatness for the city. The uncertain water supply improved after 1900 when new sources were secured. Gas lighting from the 1850s was mostly inadequate and faced strong competition from electric lighting by 1914. In 1893 Hobart became the first city in the southern hemisphere to introduce electric trams. They stimulated building in the suburbs which relieved the housing shortage for middle-class residents. Movements for a Greater Hobart were linked to these developments and by 1913 Glebe Town, Wellington, Mount Stuart and Queenborough had been amalgamated with Hobart. If in terms of municipal government Hobart was becoming a modern city, its economy remained precarious and employment uncertain, especially during the period 1858 to 1872, the 1890s depression and the early years of federation. Industrialisation was slow to develop, but Henry Jones' jam factory was a profitable enterprise. Tourism was a mainstay from the 1880s and the port thrived. Poverty received more attention in the 1880s with the appearance of the Salvation Army and a revitalised Hobart City Mission. The Salvos' work among prostitutes and the superfluity of pubs belied claims that Hobart was a moral, sober crime-free city as did the numerous neglected, vagrant and criminal boys and girls. From the 1860s their needs were ministered to by institutions such as the Girls' Industrial School, Kennerley Boys' Home and the Boys' Training School. Educational opportunities broadened with more independent schools and government schools established, notably the Model School in Battery Point (1883) and the Hobart Technical College (1888). Cultural life was enhanced by the incorporation of the Tasmanian Public Library (1870), the upgrading of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (1885) and the establishment of the University of Tasmania (1890). Literary and debating societies flourished and many clubs were formed, ranging from the Tasmanian Club (1861) to Working Men's Clubs. The Hobart Choral Society, Philharmonic Society and Orpheus Club provided concerts and musical entertainments. The City Hall (1915) allowed large crowds to attend entertainments. Hobartians banded together to further sports, with sailing, rowing, bowling, royal tennis, golf, polo, cricket and football clubs. In 1870 the Hobart Bathing Association had opened men's and women's baths, and municipal recreation areas were improved at Mountain Park and Long Beach. By 1914 Hobart and suburbs, with 39,914 residents, rivalled other Australian cities in its attractions and was more outward-looking, confident and progressive than it had ever been. Like other Australian cities, Hobart was busy during the First World War with recruiting drives and fund raising to provide comforts for troops. Trade suffered due to shipping problems, but revived in the 1920s. Fruit processing and new industries, notably the Electrolytic Zinc Works (1916) and Cadbury (1920), provided employment for many, and suburbs grew. Electricity, water and sewerage were gradually extended to them, and roads were improved to cope with heavier motor traffic. A fine sports oval was developed at North Hobart (1920). The city suffered in the 1930s Depression as did all Australia, but there was rapid development in the later 1930s, notably in transport, with an airport at Cambridge (1935) and a bridge across the Derwent, finished in 1943. Progress halted during the Second World War, when Hobart was defended from possible attack by Fort Direction at the mouth of the Derwent. After the difficult post-war years with many shortages, Hobart prospered in the long boom of the 1950s and 1960s. Industry developed with plentiful hydro-electricity, and there was little unemployment. With the Southern Regional Water Scheme (1954) all houses had running water and, soon afterwards, sewerage. Suburbs such as Bellerive and Taroona developed apace, and though central Hobart's population remained static, the population of greater Hobart rose to 120,000, including many European immigrants. Hobart gained a new university site at Sandy Bay, and the city centre was transformed by new retail and office buildings. Many sports venues were developed. Debate developed over destroying historic buildings to provide space for the new, and in the 1970s guidelines were laid down to protect Hobart's heritage. There was also debate about the form of new buildings, such as the Marine Board Building and a proposed international hotel, and from the 1970s Hobart citizens vociferously defended their city against what they saw as unsympathetic change: a cable car up Mount Wellington, or overdevelopment of the Domain and Battery Point. The Green movement has many supporters in Hobart, and the central electorate, Denison, is one of the greenest in Australia. Some industry faded and use of the port declined from the 1970s – Hobart is Australia's least industrialised capital city – but with its many colonial buildings and beautiful site, it developed as a tourist centre. The weekly Salamanca Market has been a drawcard since 1972. First-class accommodation increased with the Wrest Point Casino (1973, Australia's first) and the International Hotel, many fine restaurants opened, and with Hobart the finish of the Sydney-Hobart yacht race, festivities were organised at this season: the Tasmanian Fiesta, and more recently the Taste of Tasmania. The visit by the Tall Ships in 1988 showed Hobart at its liveliest. Moves to amalgamate local government areas failed, but by 2004 greater Hobart was a fine city of 153,000 inhabitants, and the city celebrated its bicentenary in 2003–04 with some enthusiasm. Further reading: L Bethell, The valley of the Derwent, Hobart, 1958; P Bolger, Hobart Town, Canberra, 1973; A Alexander & S Petrow, forthcoming history of Hobart City Council; J Brown, “Poverty is not a crime”, Hobart, 1972. Alison Alexander and Stefan Petrow |

Copyright 2006, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies |