The Abject Thylacine

|

The first European illustration of a thylacine was modeled on an injured animal caught in a trap. It is a sad embodiment of initial contact between Europeans and colonial fauna. The thylacine is pictured with a Tasmanian devil that was loaded onto a ship for transportation to England, but died before the vessel left Hobart. The injured thylacine also died.

The image was published in volume 9 of the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London in 1808.The engraving was produced from a drawing by George Prideaux Harris, Deputy Surveyor-General of Van Diemen’s Land, as Tasmania was called until the middle of the nineteenth century. Harris sent his drawing to London with a letter to Sir Joseph Banks speaking of "descriptions of the life" of two species, which he considered were "in every respect new". He classified the two animals in the same genus as opossums, naming the thylacine Didelphis cynocephala (dog-headed opossum) and the Tasmanian devil Didelphis ursina (bear opossum).

Harris’s notes explain that the thylacine was a male “caught in a trap baited with kangaroo flesh” and that it “remained alive but a few hours, having received some internal hurt in securing it”. His words and their syntax imply he found the situation somewhat distressing, but his fear is also apparent as he comments that the animal in the trap bore “a near resemblance to the wolf or hyæna” and that its eyes were “large and full, black, with a nictitant membrane, which gives the animal a savage and malicious appearance”.

This illustration and description encapsulate the anxieties and aspirations of early settlers in Van Diemen’s Land.

|

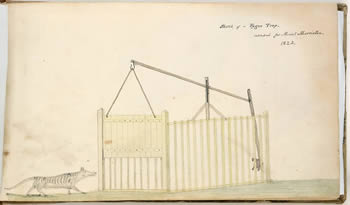

Sketch of a Tyger Trap intended for Mount Morriston,

Thomas Scott 1823.

Mitchell Library,

State Library of New South Wales.

enlarge image

|

If accounts from Port Jackson and some persons who have been here can be credited, a quadruped not quite so pleasant [as the kangaroo] to live in the neighbourhood of, is also an inhabitant of Van Diemen's Land — Traces of a Carnivorous Beast have been found in many parts, like a leopard or Panther, but I do not hear that any person belonging to the Settlement has seen the animal itself — Labillardiere in his Voyage in search of Perouse in 1792 Speaks of being ashore here & being disturbed by the Howlings of a Beast, that came pretty near them — That at another time a quadruped the size of a large Dog sprung from some Bushes — it was whitish Spotted with black — and in the woods they found a large upper Jaw and Vertebrae of an animal certainly carnivorous. I suspect however that it may be only a variety of the wild Dog, or rather wolf of this Country.

George Prideaux Harris, February 12, 1804. From Barbara Hamilton-Arnold, Letters and Papers of GP Harris 1803-1812, 1994.

|

Copies of Harris’s image

Copies of Harris’s image developed the idea of an animal in need of extermination. Mountains and forests appeared in the background, then claws are drawn on all of the animal’s feet, and soon texts began to make reference to sheep-killing. Read more

Painting of a thylacine by John Lewin, c1817.

By permission of the Linnean Society of London.

enlarge image

|

Zebra or Dog-faced Dasyurus

In Baron Georges Cuvier, The Animal Kingdom, 1827.

Wood engraving.

enlarge image

|

Dog-head Thylacinus.

Dog-head Thylacinus.

In The Pictorial Museum of Animated Nature, c1850.

Wood engraving.

enlarge image |

Dasyure Cynocephale in M.A.G. Desmarest,

Mammalogie: ou Descriptions des Especes de

Mammiferes, 1820. Wood engraving.

enlarge image |

The common names given to the thylacine influenced responses to the species. During the first decades of European settlement the species was often called 'native hyena' and 'zebra wolf' – references to European animals that were hated or feared. |

Encounter with a Tasmanian Tiger

La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria |

Although by nature a coward, this savage fights with uncommon ferocity when driven to close quarters … but human strength and human contrivance were against the brute, which, after quarter of an hour’s desperate resistance, fell dead under the blows of its protagonist, administered as depicted in our engraving

Encounter with a Tasmanian Tiger. Illustrated Melbourne Post, March 27, 1867

|

Images in natural history works, newspapers and magazines, together with their texts, were one of the means by which negative constructions of the species were disseminated. Pictures had a crucial role in both influencing and expressing attitudes and actions toward individual thylacines and the species as a whole. In 1830 the first bounty was imposed on the thylacine.

|

Engravings

Almost all illustrations of the thylacine produced in the nineteenth century are some form of engraving. Most of the images above are either wood or steel engravings, which were used extensively in the illustration of magazines, catalogues, books and newspapers.

When woodcuts could not supply enough detail to cope with the complicated taxonomy required to classify the new creatures reported by colonial explorers and settlers, engraved copper plates were used. But steel supplied an even more robust material from which thousands of impressions could be made. As the process of printing metal engravings is quite different from printing type, these illustrations are grouped together without type and are often placed at the back of the book, rather than spread throughout as are wood engravings.

Engravings are made up of lines produced by elliptical tool marks; they retain an incised quality and are distinct and definite. They were therefore considered ideally suited to illustrating scientific works. Most wood engravings are black and white, with no addition of colour to the printed image; occasionally they were hand-coloured, sometimes by subsequent owners of a book.

The same tools were used for wood, copper and steel engravings, all of which were capable of producing very fine detail. Metal engravings were particularly effective in suggesting fur, textured skin and feathers.

|

|