Six years ago, a project aiming to restore vital habitat for Tasmania’s native wildlife began with the planting of 1000 seedlings at farming properties across the Midlands.

Led by Greening Australia, the Tasmania

Island Ark program saw landholders, researchers and the community

collaborate to create a stronghold for some of our most critically endangered

animals.

Research into how

the animals used the landscape informed how the restoration plantings were

configured, including what features individual animals require to find food

while avoiding predators.

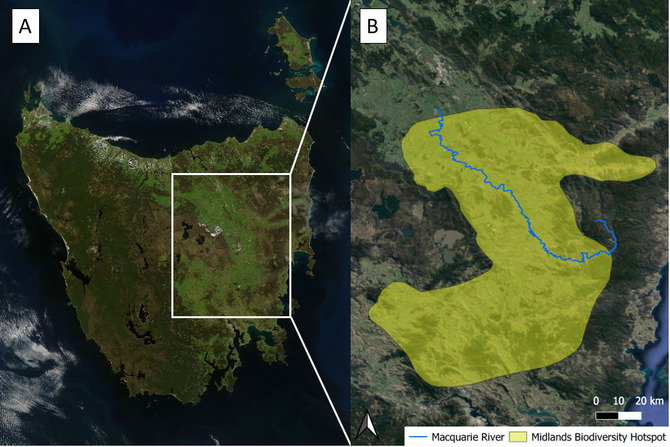

Mixed eucalypt and understorey plantings were used to build

habitat corridors, linking remnant core habitats between Cressy and Ross in

central Tasmania. To date, 144 hectares of dense plantings along the Macquarie

River and 317 hectares of wide-spaced plantings linking remnant woodlands have

been completed across the Northern

Midlands Biodiversity Hotspot.

A satellite view of the Northern Midlands Biodiversity Hotspot.

Now, researchers from the University of Tasmania are assessing the value of these restoration plantings by monitoring how native animals have responded to them.

The team surveyed three groups—ground-dwelling invertebrates, birds and terrestrial mammals—and compared community composition in plantings with those of nearby livestock pasture and remnant woodlands.

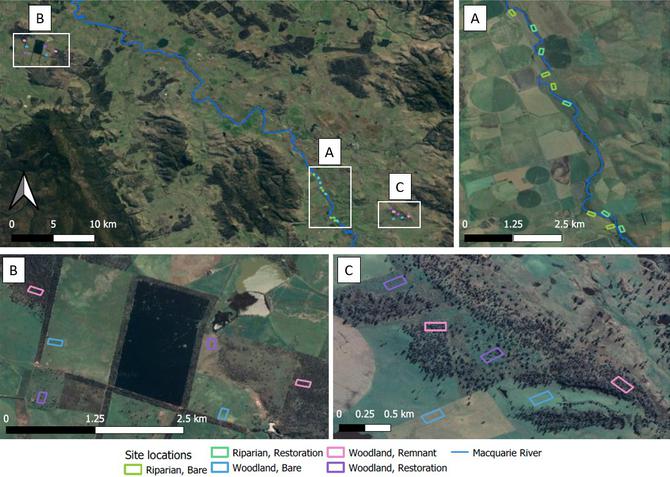

(A) riparian sites and (B) northern and (C) southern sites nearby remnant woodlands within the Midlands Biodiversity Hotspot between Cressy and Ross.

School of Natural Sciences student Kawinwit (Ink) Kittipalawattanapol,

who led the monitoring effort as part of their thesis, said the plantings were starting

to provide new habitats for small native birds and mammals.

“Our camera surveys showed that restoration plantings near

remnant woodlands play a critical role in protecting woodland mammals such as the

threatened eastern bettong,” Ink said.

These plantings form connective corridors between the animals’ core habitats, providing cover from predators. Having access to this habitat will be key to sustaining populations of the eastern bettong long-term.

The researchers also found that:

> Feral cats were most

abundant in the remnant woodlands around restoration plantings, possibly

because they prefer habitats with structural complexity and focus their hunting

activity on woodland-open pasture edges. As the plantings develop structural

complexity, however, feral cats may start to invade the restoration plantings.

> Small native insectivorous

birds, which are vulnerable from aggression by noisy miners in degraded

agricultural woodlands, used the restoration plantings alongside remnant

woodlands as refuge.

> Large-bodied birds, such as

forest ravens, were also found in early-stage plantings, particularly in the

riparian (river) areas.

> Wide-ranging marsupial

carnivores, including spotted-tailed quolls and Tasmanian devils, were recorded

throughout the Midlands landscape, including in riparian plantings.

Despite these promising signs, Ink warns that monitoring

will need to continue as emerging threats from invasive species may become

significant if left unattended.

“We found high numbers of deer in restoration plantings near

remnant woodlands,” Ink said.

“Uncontrolled deer populations are a problem, mainly because

males can cause significant damage to young trees when rubbing the velvet off

their antlers. This can result in suppressing new growth and reducing habitat

complexity as the plantings mature.”

Deer are an ongoing threat to young trees in restoration planting.

The findings from this research, published in the Journal

of the Society for Ecological Restoration, will be used to help inform

future restoration and management strategies.

The Tasmania Island Ark project is a local example of the United Nation’s Decade on Ecosystem

Restoration global initiative.