The Society of Friends in Tasmania remained perilously small. There was little new blood. Only thirteen members, including the two travellers ‘under concern’, attended the Yearly Meeting in 1853. ‘That there are no fresh enquiries after the truth and no convincements among them’, wrote Mackie, ‘is discouraging’. 27

The colony itself was losing its share of British migrants and an alarming number of its own people to Gold Rush Victoria. The survival of the Quakers depended on the younger generation. Francis and Anna Maria Cotton, Mackie was pleased to report in 1852, had twelve children, but he noted that two of the sons were at the diggings. Two years later, however, he reported that the family was ‘now a good deal broken up into separate households’, but most lived locally, and four at home. 28

George Washington Walker had ten children, but was anxious about their education. His eldest son, James Backhouse Walker, was precocious. George taught him at home until he was seven years old and then sent him to the newly established Hobart High School. After two years, he withdrew him, concerned about his lack of progress and wishing him ‘surrounded by better influences.’ 29 He undertook the considerable expense of sending him to England to Friends’ School at Bootham in York. As he wrote to his old colleague James Backhouse, ‘there are many drawbacks in the rearing of children in these colonies, more particularly in the present, disjointed state of society, consequent on the discovery of the goldfields’. 30

There were a series of attempts to establish Quaker schools in Hobart. George Walker’s hope was that James would return from Bootham and open a school. It was James’s realisation that he could not accept this destiny that led him to resolve to spare his father further expense and return to Tasmania in 1856. Coincidentally enough Frederick Mackie returned to Hobart with his young wife in this same year. They established a day-school that met with some success until, in 1861, the couple decided to return to South Australia for medical reasons. Among their first pupils was Joseph Francis Mather (1844-1925), who later wrote appreciatively, ‘Our Friends did their duty by the scholars, and a useful education was imparted, including land-surveying for the elder boys; also gardening and drawing from nature to all who would take advantage from such teaching’. 31

The problem of educational provision was by no means limited to Tasmania, and the Quakers in Melbourne attempted to establish a school. The Society of Friends in England offered assistance and advice. They saw the need for resources to be concentrated in one institution that could serve as a rallying-point for Australian Quakerism. They sent out a deputation in 1875 that found the state schools negligent in religious instruction and ‘frequented by larrikins’, and recommended Melbourne as the most suitable venue. 32 The Victorian Friends sat on their hands, and a threat to the non-sectarian status of Hobart High School in 1885 spurred the Tasmanians to action and gave them their opportunity.

The scheme for a Friends’ School in Hobart moved forward with surprising speed. J. F. Mather, now the leading light of the Quakers in Hobart, was already in correspondence with Edwin Ransome, an influential member of the Continental Committee in London. Funds were raised and commitments made, and a principal was selected. Samuel Clemes, a former missionary in Madagascar and currently headmaster of Wigton School, Cumberland, was eager to emigrate to Australia.

Edwin Ransome : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

Samuel Clemes, the first principal of the Friends School in Hobart : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

Clemes immediately became involved in the planning of the school. It would be non-proprietary, co-educational and take boarders. While the English Friends would guarantee its finances in the first years, it was a risky venture for the Australian Friends. Crucial to its viability was the enrolment of children of non-Quakers. It was an advantage here that many Protestant parents outside the Anglican communion felt able to support it. From the outset, though, the emphasis was on the high quality of the education. It was noted that Clemes was an experienced lecturer on scientific subjects, and that his wife was proficient in French and German. In the luggage that Clemes brought to Hobart late in 1886 was the latest laboratory equipment and a collection of 243 lantern slides. 33

|

|

| Classroom and laboratory at Friends' School during the time Clemes was the headmaster: University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

On 31 January 1887 the Friends’ School opened its doors to thirty-three pupils. By the end of the year its enrolment had doubled. During 1888 negotiations began for the purchase of the property known as Hobartville in North Hobart, and the school moved from Warwick Street to the new site at the beginning of 1889. There were ructions ahead, and Clemes was to resign in 1900, but the school survived and prospered.

The opportunity for a Quaker education in Tasmania came too late for James Backhouse Walker. On his departure for England Robert Mather, his grandfather, wrote: ‘I should be delighted to see thee return as a scholar, but much more a simple, devoted Friend’. 34 During the voyage and his time at Bootham James developed intellectually, but lost his sense of vocation. The experience was emancipating and exhilarating. His journals and letters reveal the thrill of his engagement with the wider world of man and nature.

On his return to Hobart he parted company with the Friends. He confided in his diary his distaste for the cold formalism of contemporary Quakerism that was ‘only redeemed from contempt by its practical, if rather fuddishly overstrained philanthropy’. He later wrote, more charitably: ‘At an early age I burst the bonds and have strayed far and wide over the spreading fields of literature and fiction, but yet I hold those simple people in honour as men whose moral fibre was better’. 35

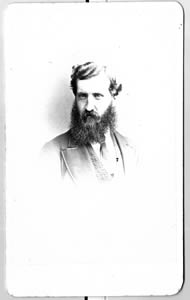

J ames Backhouse Walker 1897

University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

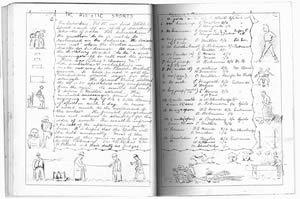

James Backhouse Walker's diary (and pencil) documenting his walk to the west coast of Tasmania, 17th Feburary 1887 to 5th March 1887

James Backhouse Walker's diary (and pencil) documenting his walk to the west coast of Tasmania, 17th Feburary 1887 to 5th March 1887 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

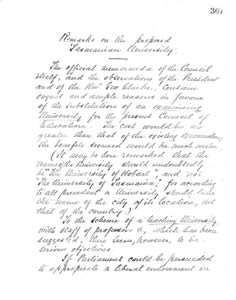

J.B. Walker left the Quakers, but was not lacking in moral fibre. A distinguished barrister, he was a champion of good causes. Ironically enough, he followed his father in his championship of public, non-denominational education. He served as a trustee of Hobart High School, and played a leading role in the establishment of the University of Tasmania. Among his papers is the firm expression of his view in 1889 that the university should be named the University of Hobart, ‘for according to all precedent a university should take the name of the city of its location, not that of the country’. 36 Oddly, given the Quaker connection, he overlooked the example of the University of Pennsylvania. He served on the council of the new university, and was its second vice-chancellor from 1898-9.

"Remarks on the proposed Tasmanian University" by J.B. Walker 26th August 1889 from his letterbook : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

Newspaper clipping of letter, 6th July 1898

Newspaper clipping of letter, 6th July 1898 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections |

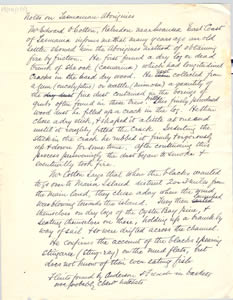

His interests and expertise ranged across the humanities and the sciences. He combined oral history with fieldwork in natural history. A prominent member of the Royal Society, he was one of the leaders and the chroniclers of an expedition to the west coast of the island. 37 He knew more about Tasmania — its geology, its flora and fauna, its peoples — than anyone before or since. He undertook extensive research on the Tasmanian aborigines, challenging such myths as their inability to make fire. In a letter to a local newspaper in 1898, he acknowledged the offence he had unintentionally given to people of Aboriginal descent on the Bass Strait Islands by failing to mention ‘the well known fact that in the Strait Islands at the present day there is a considerable population having Tasmanian aboriginal blood in their veins’. 38

|

Samuel Clemes and his staff, 1892:

University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

The first Friends' School Sports as reported in School Echoes, the Friends High School Magazine no 3, XI,1890 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

The Friends' girls cricket team, view from front classroom 1891 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

Bruny Island Friends' school picnic 1890's : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collection

Friends' High School in the 1890s

James Backhouse Walker with his sisters, Mary (back) Isa and Sarah : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

James Backhouse Walker journal of his sea voyage to England aged 12 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

James Backhouse Walker : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

Walker's Notes on the Aboriginies of Tasmania, Royal Society of Tsmania 1898 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

Walker's Notes on the Aboriginies of Tasmania, 1898 : University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collections

|

Footnotes:

27. Nicholls, Traveller under Concern, p. 157.

28. Nicholls, Traveller under Concern , p.. 54.

29. Backhouse and Tylor, Life and Labours of George Washington Walker, p. 530.

30. W. N. Oats, The Rose and the Waratah. The Friends’ School Hobart. Formation and Development, 1832-1945 . Hobart: The Friends’ School, 1979, p. 39.

31. J. F. M.’s schooling’, R7/111 (2), University of Tasmania, Special and Rare Materials Collections.

32. Oats, The Rose and the Waratah , pp. 47-8.

33. Oats, The Rose and the Waratah , pp. 59.

34. Oats, The Rose and the Waratah , p. 29.

35. Oats, The Rose and the Waratah , pp. 35-6.

36. J. B. Walker, ‘Remarks on the proposed Tasmanian University’ [1889]. W9/C2/3 (367), University of Tasmania, Special and Rare Materials Collections.

37. J. B. Walker, Walk to the West , ed. D. M. Stoddart. Hobart: Royal Society of Tasmania, 1993.

38. Newspaper clipping of letter, 6 July 1898. W9/C4/1 (29), University of Tasmania, Special and Rare Materials Collections.

|

Quaker Life in Tasmania Home | UTAS Library Home |