A Tasmanian devil expert has uncovered an evolutionary quirk that sets carnivorous marsupials apart from the crowd – and the secret lies behind their smiles.

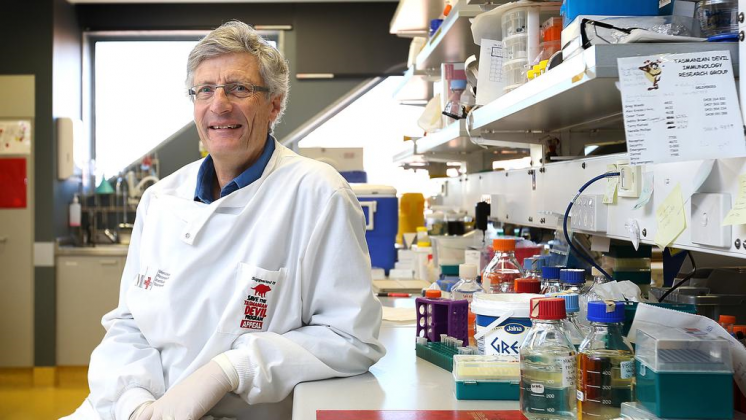

Professor Menna Jones from the University of Tasmania’s School of Natural Sciences has been studying Tasmanian devils for more than 30 years, and her latest research confirms a significant, fundamental morphological difference found in devils compared to most other animals: they only get a single set of teeth.

Professor Jones said this information helps researchers to determine the age of animals that they are studying, including those monitored in the wild for devil facial tumour research.

“Unlike humans or dogs, or many other animals that have a baby set and second adult set of teeth, we know that devils only have one set that serves them through their entire lives,” Professor Jones said.

“When a devil joey is very young it has very small teeth that fit its small body. Devils are weaned from their mothers when they’re just one-third of their adult size, and it’s at this point they have to become independent and feed themselves.

“Instead of losing time changing over to a set of adult teeth like humans do, the devil’s teeth simply “erupt” gradually out of their jaws and gums, pushing further and further out to fill the devil’s larger mouth and head, allowing the growing animal to hold meat and prey and defend itself.

“This is a very cool fact about a very cool species, and it shows a completely different evolutionary solution to having teeth in growing animals than what we’re familiar with,” she said.

The same phenomenon is seen in quolls and thylacines locally, and also in some ancient marsupial species like giant borhyaenids and sabre tooths from South America.

This research was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.