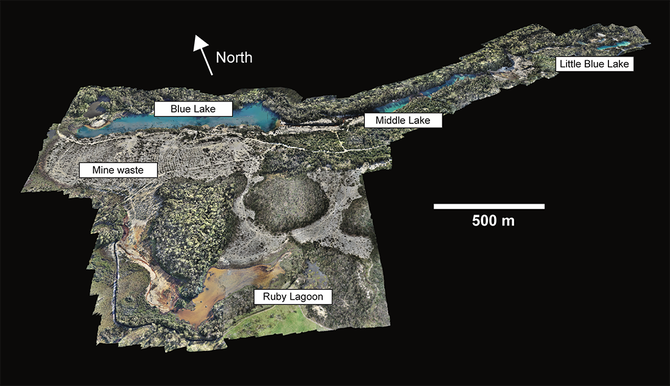

Beneath the sparkling waters of Tasmania’s ‘Blue Lakes’ lie three old open-cut mine pits that were targeted for tin.

While the pristine blue appearance attracts water skiers and swimmers, the historic mine waste from the Endurance tin mine in North East Tasmania has left a less desirable legacy.

“The lakes appear clean, but some areas are actually unsuspectingly acidic and contaminated,” up-and-coming hydrogeologist and University of Tasmania honours student Olivia Wilson said.

“Rivers and lakes impacted by mining activities tend to be quite orange due to their high metal content – it’s obvious you should not drink it or swim in it – but the Little Blue Lake is a lot clearer so there’s less awareness that it’s a contaminated site.

“We think the blue appearance is a reflection from small clay particles which exist in the Little Blue Lake in high amounts,” she said.

The Blue Lakes were originally open-cut pits from an old tin mine.

The legacy of an old tin mine

From 1874 to the early 1980s, miners extracted tonnes of tin from the Endurance tin mine within the eucalypt forests of North-East Tasmania.

Now under management of the Tasmanian Government, the site is known as a ‘legacy’ mine because the mining company is officially no longer responsible.

When mines close, what is left behind are the tailings or mining waste, which is mostly made up of non-valuable minerals. At some mine sites, the mining wastes contain a particular group of minerals known as sulphides.

“When the sulphides are underground they are typically stable, but when dug up and exposed to oxygen and water, some sulphides oxidise and you end up with an acidic fluid which is capable of breaking down other minerals and liberating metals out of the mine wastes,” Olivia explained.

This process is known as acid mine drainage and is the focus of Olivia’s research.

Barren land: Mine waste left behind at the legacy Endurance tin mine.

Contaminants are leaching out of the mine waste into waterways.

“The contaminated water may eventually find its way into natural environments and, in some cases, it can completely decimate them,” she said.

“You see this with the King-Queen river system, Tasmania’s most famous example. It is barren and very little life can survive in those conditions.”

Fortunate field trips after lockdown

Olivia is one of three Centre for Ore Deposit and Earth Sciences (CODES) and Transforming the Mining Value Chain (TMVC) environmental geology honours students working to understand the Endurance site and prevent further contamination.

This year Olivia and fellow students Eliza Fisher and Wei Xuen Heng visited the Endurance site twice to obtain water and sediment samples, and geophysical data for their respective research projects.

Following extra safety planning, preparation, and equipment to meet public health requirements, the team got stuck into fieldwork just a month after the Tasmanian COVID-19 lockdown.

“Fortunately, we were able to get water samples, which showed some interesting patterns. Some of the lake had acceptable water quality, while others had high levels of acidity and poor water quality. We saw a similar pattern in the groundwater around the site.”

Olivia Wilson assesses the minerals that remain in the mine waste.

Olivia is researching how the flow of groundwater through the legacy mine wastes at Endurance is generating and transporting contamination to the downstream environment.

“I am looking at the flow of groundwater by measuring water heights and some properties of the aquifer sediments. From this, I can figure out the direction and rate of groundwater flow and make inferences about the movement of contaminants,” she said.

All three honours projects are funded through the Mining Sector Innovation Initiative Program, a collaboration between Mineral Resources Tasmania (MRT), TMEC and CODES/TMVC at the University of Tasmania.

During the first field trip in June 2020, MRT staff joined the crew at Endurance and supported the collection of ground and surface water samples, and drone imagery.

Aerial view of the legacy Endurance mine site, North-East Tasmania.

Career connections and a love of nature

“During my honours project I’ve had fantastic support from my University supervisors, MRT and mentoring in hydrogeology from GHD, a consultancy firm in Hobart,” Olivia said.

“One of the great things about studying in Tasmania is it’s a small community so you get to create close connections with lots of people.

You get to meet professionals in the field with unbelievable ability and knowledge.

Olivia’s outdoorsy family meant she grew up camping, boating, fishing, and basically spending as much time outside as she could.

“From a young age I’ve always been passionate about protecting natural environments and leaving pristine places for future generations to enjoy,” she said.

In 2021 Olivia hopes to be working as an environmental scientist in Tasmania, and she plans to stay here for at least the next 5 years.

“I really love it here. I love the diversity of Tasmania. You can drive for three hours and feel like you’re somewhere else. It’s pretty awesome.”