Korongee Dementia Village: Source Glenview Community Services

Background

In a decade, the number of people living with dementia worldwide has risen from 35 million to 50 million (Wimeo et al., 2013; ADI, 2021). With the growing population of people living with age- related dementia, there is a growing need for purpose-built residential aged care facilities (Feng et al., 2012; Gaugler et al., 2014; Sun & Fleming, 2018). Despite the visible need, many aged care facilities cannot meet the care and environmental needs of their residents living with dementia (Sun & Fleming, 2018; Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2021). Care staff struggle to deliver dementia care in environments that remain pathogenic (Sun & Fleming, 2018).

Pathogenic designs prioritise organisational efficiency in the effective treatment of diseases. These designs focus on disease, disability, and loss, which is inimical to the care and wellbeing of people living with dementia.

Enabling Environments in Aged Care

A vital aspect of dementia care is providing an enabling environment, especially in long-term care facilities. The understanding that built environments can enable, enhance, and empower people living with dementia has been growing in the last three decades (Fleming, Zeisel, & Bennett, 2020). The body of evidence also suggests that the built environment can support the person living with dementia to attain their full potential and benefit the people and community around them (Calkins, 2018; Fleming, Zeisel, & Bennett, 2020). However, there is a gap in the knowledge and application of dementia enabling environments (Sun & Fleming, 2018; Fleming, Zeisel, & Bennett, 2020).

Research on aged care facilities in East and Southeast Asia found a lack of awareness of dementia and positive care environments for people living with dementia (Sun & Fleming, 2018). Within these regions, staff trained in dementia care were found to have little or no knowledge of dementia enabling environments, which is a supportive component in dementia care (Sun & Fleming, 2020a). In Australia, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021) recommends that new aged care accommodations should incorporate designs that are accessible inclusive for people living with dementia. Non- purpose-built environments continue to be a significant barrier attributed to the inability to provide quality dementia care. Non-purpose-built environments promote disengagement and disability for residents and become operational barriers for staff (Sun & Fleming, 2018). An additional barrier preventing the facilitation of quality dementia care within an enabling environment for residents living with dementia is the lack of an aligned or supportive model of care.

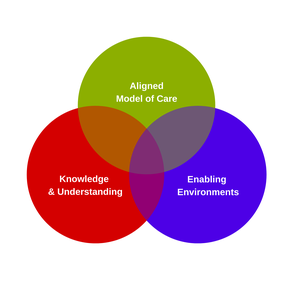

Model of care is an aged care service design underpinned by evidence-based practice, theoretical foundations, and clear standards (Davidson et al. 2006). A supportive model of care can bring together an organisation to reach its goals and assess key outcomes (Davidson et al. 2006). Staff working in dementia enabling environments and equipped with the knowledge and understanding of enabling environments found that without a supportive model of care, purpose-built environments become underutilised or repurposed (Sun & Fleming, 2020b). Reviewing the evidence, some of the critical components that are vital in the creation of sustainable enabling and inclusive environments for people living with dementia include,

- equipping staff with knowledge of dementia enabling environments and its' role in dementia care;

- the incorporation of dementia enabling environments; and

- an aligned model of care (Box 1).

Box 1: Key components that are vital in the creation of sustainable enabling and inclusive environments for people living with dementia.

In Australia, a study of 17 residential aged care facilities found that 83 per cent of residents were living with cognitive impairment and approximately 65 per cent had a diagnose of dementia (Dyer et al., 2018). Korongee, a village for residents living with dementia, is ahead of the curve, addressing the gap arising from the changing care and environmental needs of Australians living with dementia in residential aged care facilities. The village opened in July 2020 can be found in the northern suburbs of Hobart in Tasmania, Australia. Lucy O'Flaherty, the CEO of Glenview Community Services, had observed the evolving need for services,

"The demographic in our community and those that were seeking service changed so much that not only was the physical environment no longer conducive to good care, but the care model needed to evolve as well. Many of our facilities have been purchased in the 40s, 50s, 60s, added on, added on, added on, through a good mixture of our communities, but they would no longer fit for purpose. So long corridors, workflows which meant in existing facilities you get from one corner of the building to the other, you take about 15 minutes. Which is not conducive if you are having to respond to an emerging critical situation."

She describes Korongee as the first of its kind in Australia in its impact and offerings for residents. The village design centres on the residents’ needs and aims to provide dignified therapeutic value, contributing to residents' quality of life. Korongee is a combination of dementia design, technology, a unique model of care and the use of an evidence-based resident matching tool. The environmental designs have translated knowledge into action by developing a purpose-built village that embodies the Fleming-Bennett principles of design, recognised as an international evidence- based best practice (Fleming, Zeisel, & Bennett, 2020, Box 2).

Box 2: The principles of designing for people living with dementia

1.

Unobtrusively

reduce risks

2.

Provide

a human scale

3.

Allow

people to see and be seen

4.

Reduce

unhelpful stimulation

5.

Optimise

helpful stimulation

6.

Support

movement and engagement

7.

Create

a familiar place

8.

Provide

opportunities to be alone or with others

9.

Link

to the community

10. Design in response to vision for way of life

Source: Fleming, Zeisel, & Bennett, 2020, p. 13

Korongee adopts a salutogenic approach, focusing on the residents' wellbeing through a household model for 12 houses in the village. The household model provides a home-like experience for residents, in an environment that is familiar and safe. The model, coupled with an enabling environment and a supportive team of staff, empowers residents to live dignified and inclusive lifestyles. The village includes a community centre, wellness centre, cafe, salon, a general store, and a range of spaces where residents can engage in groups or step aside for quiet time alone.

Raymond Plant whose wife is residing in the village provided the following observation (Commane, 2021),

“You’re not all crowded into one room or in one complex, like some of the nursing homes. So yeah (sic), it is a lot different. A lot better. Here it is more relaxed. It’s like living at home.”

Residents have full visual access into the general store from the entrance. Source: Glenview Community Services

The village is also inclusive of the wider community, acknowledging that aged care should not exist within its confines. The care model meets the requirements and exceeds the norm by ensuring that dignified dementia care is essential and can be sustained within the village through evidence-based practice. Relationships are a crucial aspect of the model of care. The strengths of staff are harnessed as they are allocated into areas where they thrive, building relationships with the resident, their families, support structures and care professionals. Positive relationships are crucial as it enables dialogue between the multiple vital individuals who are critical in supporting the person living with dementia.

The ability to translate learning is crucial at Korongee, with qualified staff that can translate their knowledge and experience into best practice. However, the village has yet to realise its full potential due to restrictions brought about by the pandemic. In the future, the village aims to integrate with the surrounding community, establishing a social connection with residents who may not be able to leave the environment independently.

Conclusion

The inability to translate knowledge into action continues to be a barrier in delivering dementia care in many facilities worldwide (Sun & Fleming, 2018). Korongee presents a precise execution of knowledge translation in action, showing a cohesive awareness, agreement and adoption of dementia care practices and environments (Davis et al., 2003). The village ensures sustainability through the process of adherence. This process is the consistent review of evidence-based therapeutic interventions, dementia training, and the staff's competency in the application of dementia care.

It is possible, that dignified dementia care can be delivered when a culture of knowledge and understanding permeates the organisation. There is an aligned model of care and environments that support and enable residents, families, staff, and the wider community. Countries experiencing a growing population of people living with dementia requiring residential care should consider the need for such salutogenic facilities. Korongee is one such model that can address the gaps in the provision of dementia care and enable residents living with dementia to thrive with meaning, dignity and respect in an inclusive community.

First published through Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities: https://lkycic.sutd.edu.sg/research/resources/