The governance response to climate change has undergone significant evolution over the past thirty years. Global efforts to reduce human greenhouse gases emissions have dominated climate governance at an international level.

Reducing emissions remains the highest priority for the international community, but serious progress on this front is as distant as ever, despite the 2015 Paris Agreement’s aim to limit warming to 1.5-2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The realisation is growing within the climate science and policy communities that the earth will significantly overshoot this temperature range of the Paris agreement. Current projections suggest that the planet is on a path for a 3.4 degree rise in temperature, which on most views, will be catastrophic for ecological and human wellbeing.

Climate Intervention Proposals

On the immediate horizon are a range of technology proposals for “climate intervention”, that is, deliberate human intervention in the earth’s climate system to reduce the risks and/or effects of anthropogenic climate change.

Solar Radiation Management

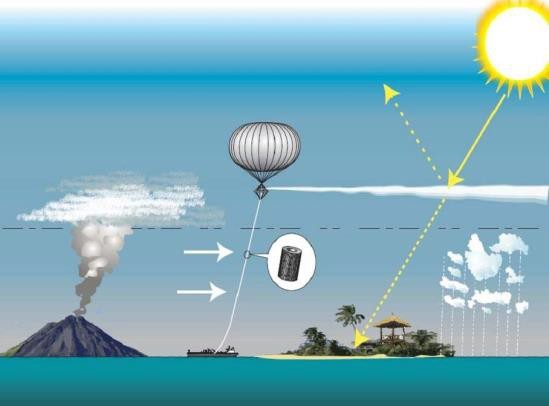

The first type of climate intervention is known as solar radiation management (SRM) because it aims to reflect into space a portion of incoming solar radiation and thereby reduce the amount of heat energy in the earth system. SRM proposals don’t address the key driver of climate change (i.e. excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere) but rather seek to mask its effects by reducing the buildup of heat energy in the earth system. Key examples of SRM proposals include stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) and marine cloud brightening (MCB).

Stratospheric Aerosol Injection

Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) proposals involve aircraft or high-altitude balloons releasing minute particles into the stratosphere to reflect a small amount of incoming sunlight. SAI is intended to mimic the climatic effects of large-scale volcanic eruptions, such as the 1991 eruption of Mt Pinatubo, which reduced the global temperature by 0.5 of a degree for 18 months.

Marine Cloud Brightening

Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) is proposed to be used on a more localised scale, for example, over the Great Barrier Reef. MCB would involve ships spraying small droplets of seawater into the lower atmosphere to increase the reflectivity of clouds, thereby lowering local or regional temperatures during high temperature weather events, which can cause damage to local ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

Carbon Dioxide Removal

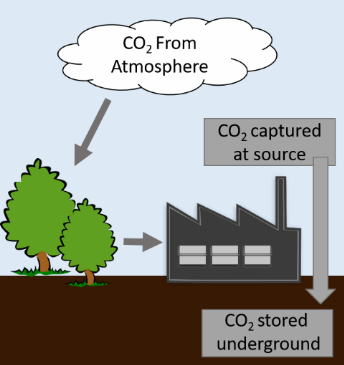

The second category of climate intervention proposal is known as Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (CDR). These CDR techniques hope to draw large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it for the long term in the land, forests and oceans.

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage

A prominent example of CDR is bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). BECCS produces energy by burning biomass, then captures and stores the carbon dioxide created in the combustion process before it enters the atmosphere. It extends earlier carbon capture and storage proposals in the energy industry and could contribute to the world’s energy supply while also producing negative emissions.

Ocean Fertilisation

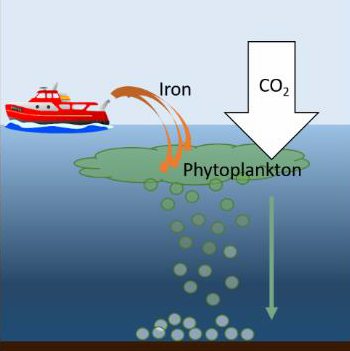

Another prominent example of CDR is ocean fertilisation (OF), which enhances the natural sequestration of carbon dioxide through stimulating the growth of phytoplankton in the ocean.

Climate Intervention Risks

Climate intervention has its own significant environmental and social risks. It may have negative impacts on the environment of the state in which field-testing and/or implementation occurs, or transboundary impacts on other states and global commons areas, such as the high seas areas of the oceans and atmosphere.

Governance of these emerging climate intervention or ‘geoengineering’ strategies has been slow to develop, with concerns that the formation of governance arrangements will detract from efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The key concern of international law has been to minimise and manage these risks. In the last decade, the 1992 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and the 1996 London Protocol on ocean dumping have adopted a highly precautionary approach that places a non-binding moratorium on all climate intervention activities, except small-scale scientific testing of ocean fertilisation, and other geoengineering proposals that are unlikely to impact on biological diversity.

However, the Paris Agreement targets might only be achieved with the help of some of these strategies, particularly CDR. For this reason, climate intervention will be the next significant phase of climate change governance at an international and national levels.